When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.Heres how it works.

Ken Levine’s work is defined by a wariness of the human animal and its capacity for cruelty.

Yet he sees himself as “deep down, a real optimist”.

“But I always had my eye on that world.

And to some degree, you have to lie to yourself and kid yourself.”

“And then it didn’t work.

“At 29, I was older than most people at Looking Glass.”

“We lost our first project, right at the beginning,” Levine says.

“I had not shipped a title, Thief wasn’t out yet, I had no money.”

Most people would quit at this point, because most people are rational.

But what if I don’t quit?

We had all these crazy ideas.

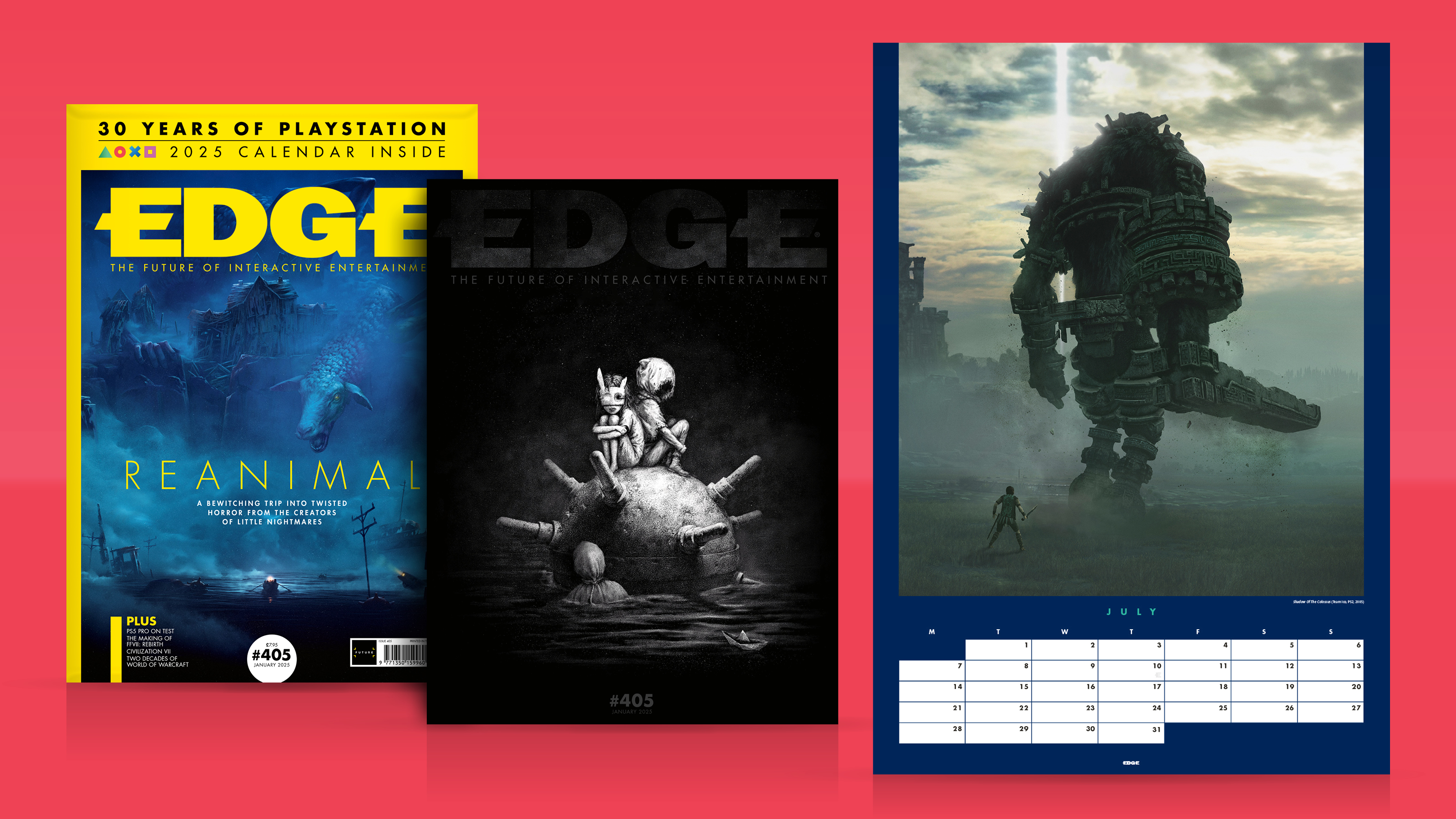

This feature originally appeared inEdge magazine.

It lined up with a lot of what we were doing in terms of the awareness cycle of enemies.

And that was quite innovative.

That was the idea that stayed.

I came up with the Trickster and the church of the Hammers.

But they were both extremes.

If you could define it, the theme of my storytelling is ‘be wary’.

I don’t know how to build a world without those themes, because they’re so present.

It happens a lot, and it often leads to dehumanisation and bad outcomes.

Whether it’s Hitler or Mao, rigidity leads to death.

I like exploring that notion, because I just find it endlessly fascinating.

And it does endlessly repeat historically, over and over.

It was an amazing company, but they struggled to be financially stable.

I had two partners who are very, very smart Jon Chey and Rob Fermier, my Irrational co-founders.

We lost our first project three weeks into it.

We had no money, no investors, and we had to scramble.

It was a very lightly funded project.

It was hopes and dreams and a little bit of money.

I’m still amazed how quickly it was done, given the Judas time period.

Nobody had really done a firstperson shooter RPG hybrid.

The interface was extremely non-standard; there was no mouselook.

But the audio voice was 100 per cent accurate.

So that was incredibly powerful.

We got involved with a publisher called Crave they were well-funded, and they were excited about us.

They started a second project with us, which became Freedom Force.

The Lost was the first console game we tried to do.

People really liked the story.

We struggled technologically to get that thing working on the PS2, which was a very strange beast.

Jon eventually came back.

But I did not have the experience to understand the technological challenge.

We kissed a lot of frogs along the way.

Eventually the publisher ran into financial problems, and they started putting the squeeze on us.

The money started drying up, and we finished the game in great conflict in terms of getting paid.

I was trying to make payroll, and it was the least fun time in my life.

The problem is they didn’t promote those games, because they made less money off that.

That’s understandable, but it was not good for Freedom Force.

That was very disappointing.

We put a lot of heart into it.

Jon had come back and had set up Irrational Australia, so we were one company with two studios.

That was a good experience.

The dialogue and attitudes are very much of their time.

Peter Parker and the great Uncle Ben story, it’s a fable.

They’re all morality plays.

That’s why they still resonate.

I wanted to take that notion, as well as the art style.

We actually heard that from journalists and publishers.

I don’t believe in curses, and I just kind of ignored it.

We showed it could be done, and then Arkham came in.

What makes a hero is sacrifice and a moral framework to work in.

Freedom Force did well, but not enough to make us any royalties.

Publishing deals were garbage back then the developer almost never made money.

I felt a little bit lost on that.

Looking back, it probably wasn’t the wisest thing for me to take on as a writer.

Then they fired them, and they brought me back to finish it in very limited time.

I had to rewrite it and get it recorded in a studio in California.

And it was fun to get fired again.

We liked the tension that was just natural in a SWAT game.

There’s no minigun or BFG.

You’re encouraged to go light, but the enemies have no such constraints on them.

It was a relatively short development cycle, and the team really pulled together.

Because I was mostly distracted, my primary contributions were helping establish the vibe of it.

Originally, it was more corridors and office buildings.

We did far better storytelling than Tribes: Vengeance in that game with far less.

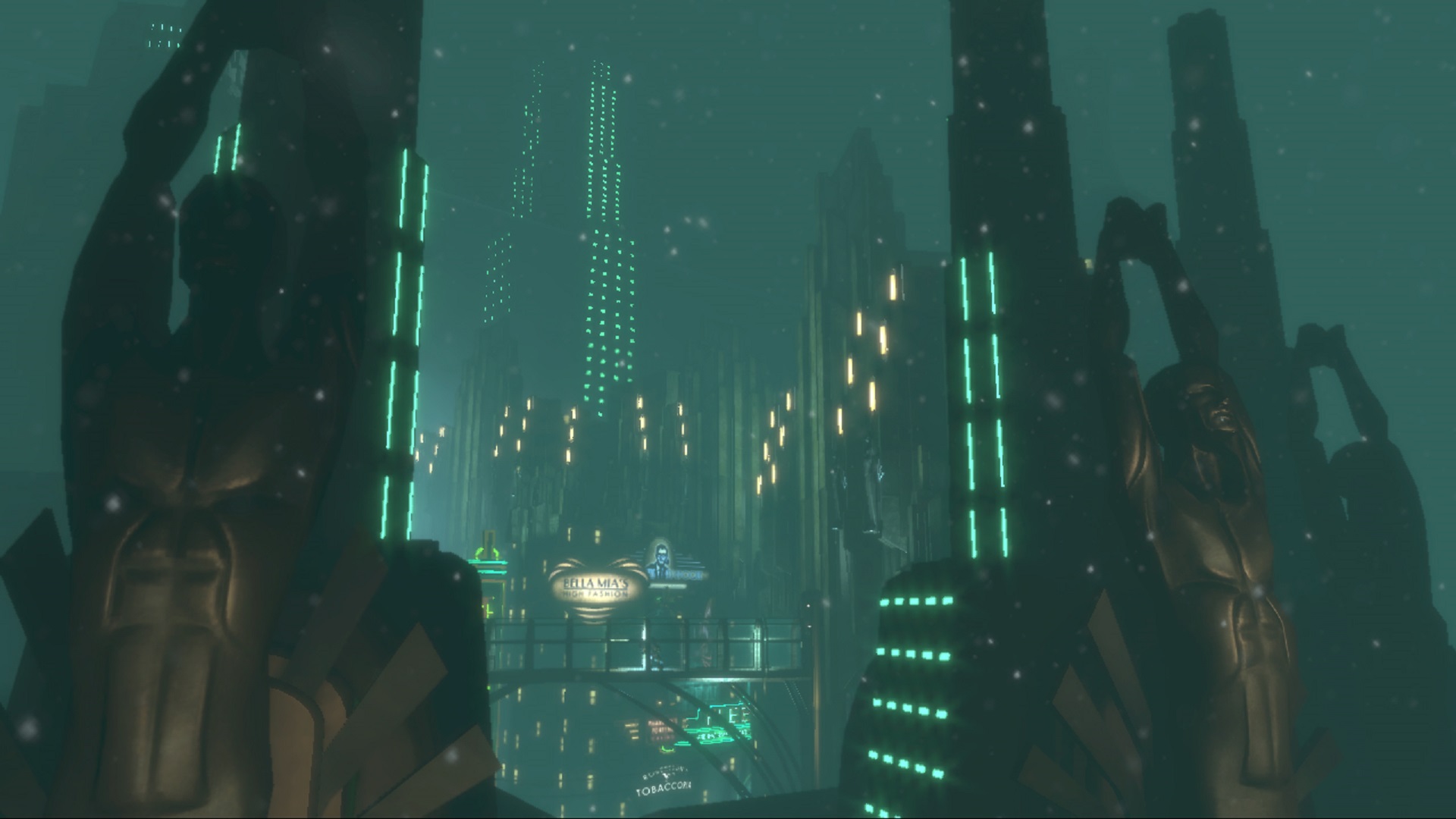

It was a really good training ground for the environmental storytelling we were to do on BioShock.

We were like, ‘We don’t really have any words how do we tell a story?’

The tools had come along a little bit since System Shock 2.

Everything was dingy in the game by design.

I think that was quite successful, and the team did a great job pulling that together.

The gameplay was good.

We improved on SWAT 3.

The creative director is the guy who has to decide what goes in the game and what doesn’t.

That’s the primary job.

Up toBioShock, I wrote almost all of the words in the games that I worked on.

And that thing has to be coherent.

I believe it’s a real role.

Somebody has to have the final say.

I also think that you have to be involved in everything.

Everything we do in game development is storytelling, from programming to office administration.

We all share the same common goal, which is we’re telling the story to the user.

To really be a creative director you’ve got to have your paws in every single thing.

And you gotta be careful not to micromanage.

But if you don’t have some degree of micromanagement, then you don’t have a consistent vision.

So world’s smallest violin it’s a tough job.

But it’s also an amazing job.

Finally, they wore me down.

We came up with something, made a cheap prototype, took it out and pitched it.

And it was frustrating.

It was a bunch of years we were working on it, going back and forth.

We were led to a guy at GameSpot, Andrew Park.

The next day, people saw the article, and we started getting phone calls.

I think it created a sense of demand in the publisher.

Very quickly after that, the game was set up.

I felt the emotion of it.

And it was the music of my father’s youth.

I talked to him and I said, “What were the songs, Dad?”

I loved working on BioShock.

It did almost get cancelled, though, right before the end.

It was going over budget and over time.

The whole infanticide angle of it, where you’re killing these Little Sisters.

The publisher was very nervous about that, understandably.

It was experimental, but it was exactly the game I wanted to make.

We were struggling to get our head around the squad control.

I didn’t have a great solution to fix it.

And his response was like, “Well, then somebody else will.”

After some complicated conversations, we ended up doing the next one after BioShock 2.

Because I didn’t want to go back to Rapture I didn’t have an idea for it.

I wanted to do something different, but the same.

There are a lot of similar themes an American story from an alternate past.

But with every game we also tried to take on a new challenge.

That was the technological challenge of that game.

It scaled to the point where I was struggling to keep everybody on the same page.

That got away from me.

I’ll put the blame on me for that, because that’s the job of the creative director.

But I was just overwhelmed by the scale of the thing.

“Some people love the gameplay and prefer it to BioShock.”

The Sky-Lines were me trying to do something action- and movement-oriented, which we hadn’t done before.

It was a big adjustment for us.

If we had done a sequel to Infinite, I think I would have spent more time on that.

That thing was built on Unreal Engine 3, which is not an outdoor engine.

Sky-Lines were a lot of spit and chewing gum and prayers.

What is the philosophical impact of a world where the many-worlds theory of quantum mechanics exists?

In terms of endings, I think it was the best one we’ve ever done.

Our team really delivered, and the actors really delivered.

I think the gameplay suffered a little bit.

But it actually turned out for the best, because people seem to like that a lot.

The closure of Irrational was complicated.

I felt out of my depth in the role.

My mental health was a mess during Infinite.

That’s why I didn’t maintain the name Irrational.

I thought they were going to continue.

My feeling was that it probably would have made sense.

I don’t think I was in any state to be a good leader for the team.

I had a lot of respect for the people on the team.

That’s not to say that didn’t suck.

Interestingly, a good chunk of those guys ended up coming back and working on the new BioShock game.

Then a bunch of them went and started their own companies.

At Ghost Story we work with a whole bunch of companies that were founded after the closure of Irrational.

The ship is broken, and you broke it.

You broke it for pretty good reasons, but was your reaction an overreaction?

I don’t like simplistic heroes and villains, because I’ve never met one.

I like these broken characters because I relate to them.

We’ve got thebest stealth gamesfor you to take a look at!

We’re also playing close attention to all thingsBioShock 4.